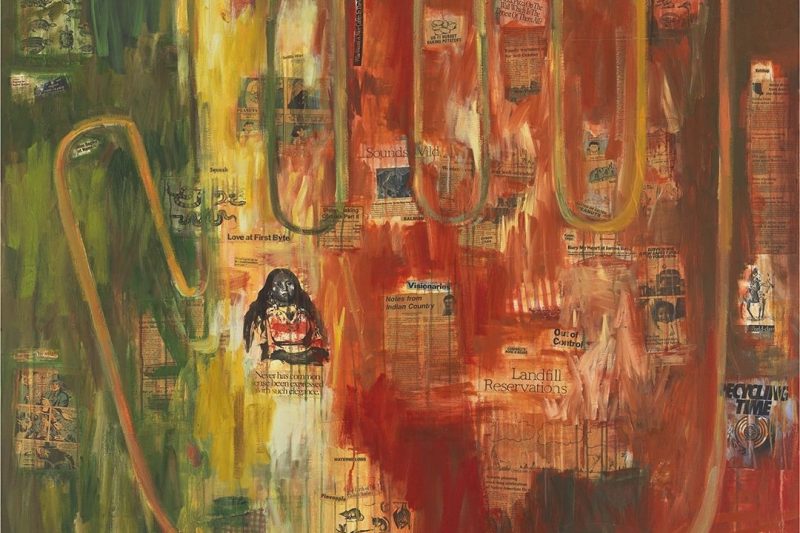

Indian Hand (I See Red) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith was among the six 2018 Governor’s Arts Award recipients, honored during a public ceremony with Lt. Governor Mike Cooney on Dec. 7 at the Capitol Rotunda in Helena. The Montana Arts Council hosted the ceremony and a reception that followed for Smith and fellow honorees Rick Bass, Monte Dolack, Jackie Parsons, Kevin Red Star and Annick Smith.

My tribe is the biggest influence in my work. How my tribe values the natural world, how they treat the animals and wildlife that reside there. How they treat our relations and value the children as well as the respect for elders.

– Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith was born in St. Ignatius and grew up on the Flathead Reservation. A Native American of French-Cree, Shoshone, and Salish blood, she’s an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

As a child, she traveled around the Pacific Northwest and California with her father, a horse trader. Smith decided she wanted to be an artist after watching a film on the French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. She painted a goatee on her face with axle grease and borrowed a neighbor’s beret so she could be photographed posing as the famous artist.

In 1958, Smith enrolled at Olympic College in Bremerton, WA, where she received an Associate of Arts Degree. She attended the University of Washington in Seattle, and earned her bachelor’s in art education at Framingham State College, MA, and a master’s degree in art at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, where she also founded the Grey Canyon group of contemporary Native American artists.

One of the most acclaimed American Indian artists today, her work has been reviewed in most art periodicals. Smith has had over 100 solo exhibits in the past 40 years and has produced printmaking projects nationwide. Over that same time, she has organized and/or curated over 30 Native exhibitions, and lectured at more than 200 universities, museums and conferences internationally, including five universities in China.

She has completed several collaborative public art works such as the floor design in the Great Hall of the Denver International Airport; an in-situ sculpture piece in Yerba Buena Park in San Francisco; and a mile-long sidewalk history trail in West Seattle.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Q&A

Smith kindly answered a few questions about her approaches to life and art-making:

Who was your greatest influence and why?

My tribe is the biggest influence in my work. How my tribe values the natural world, how they treat the animals and wildlife that reside there. How they treat our relations and value the children as well as the respect for elders. This and more impacts my work in the largest way.

Next is my father, Salish, Metis, horse trader, trainer and rodeo rider, who grew up on the Flathead and lived there into middle age. He taught me to observe nature, whether it was a hawk in the sky, the gait of a horse or tracks in the snow. His words and teachings follow me.

After my Dad passed, my husband Andy Ambrose gave me encouragement to finish college and follow my dream to be an artist and is still my biggest fan and helpmate.

My beloved cousin Gerald Slater, Salish, vice president and founder of Salish Kootenai College was my mentor too. We both believed in Indian education. Often times we would be up til 3 a.m. talking Indian politics, Indian education and telling family and tribal stories. We were passionate about Salish Kootenai College and our tribe.

How has Montana and your Salish identity shaped your art?

We, Salish and Kootenai Peoples are a trading tribe, not merchants, not hoarders, but sharing what is available. I do that with my work and my time in the name of education. I feel blessed that Director Laura Millin and the Missoula Art Museum have been welcoming toward my art and the Yellowstone Museum has been as well.

Yes, the tribe’s worldview has shaped my life and my art. For years, all the titles on the series of my drawings named places across the reservation, Arlee, Camas, Moiese, Hungry Horse and Ronan.

I am an avid reader of Montana writers and poets. Vic Charlo and Debra Magpie Earling, both Salish, and James Welch, Blackfeet, are three of my favorite writers.

The Last Best Place, edited by William Kittredge and Annick Smith, two writers I’m fond of, is another favorite book that I’ve read and reread. By the way, my granddaughter, Annick Ambrose, an excellent western rider, is named after Annick Smith.

I read all the books published by Bob Bigart at Salish Kootenai College, which are wonderful pieces of tribal history. I’ve read Montana writers for years because when I can’t be there, they carry me away in my daydreams with their descriptions of the Montana land.

Please share something about your work, process or inspiration that might not be widely known.

I’m a fervent researcher. When I start a painting, I cannot fully commit to it until I read and search for information about whatever the subject is, wherever the painting is headed. I need to know about the geography, if it’s a map; the social justice if it’s a map about people; the women’s issues if it’s about women kind of people on that map; the history of those women. This all helps me make a story in my head and guides me to the finish.

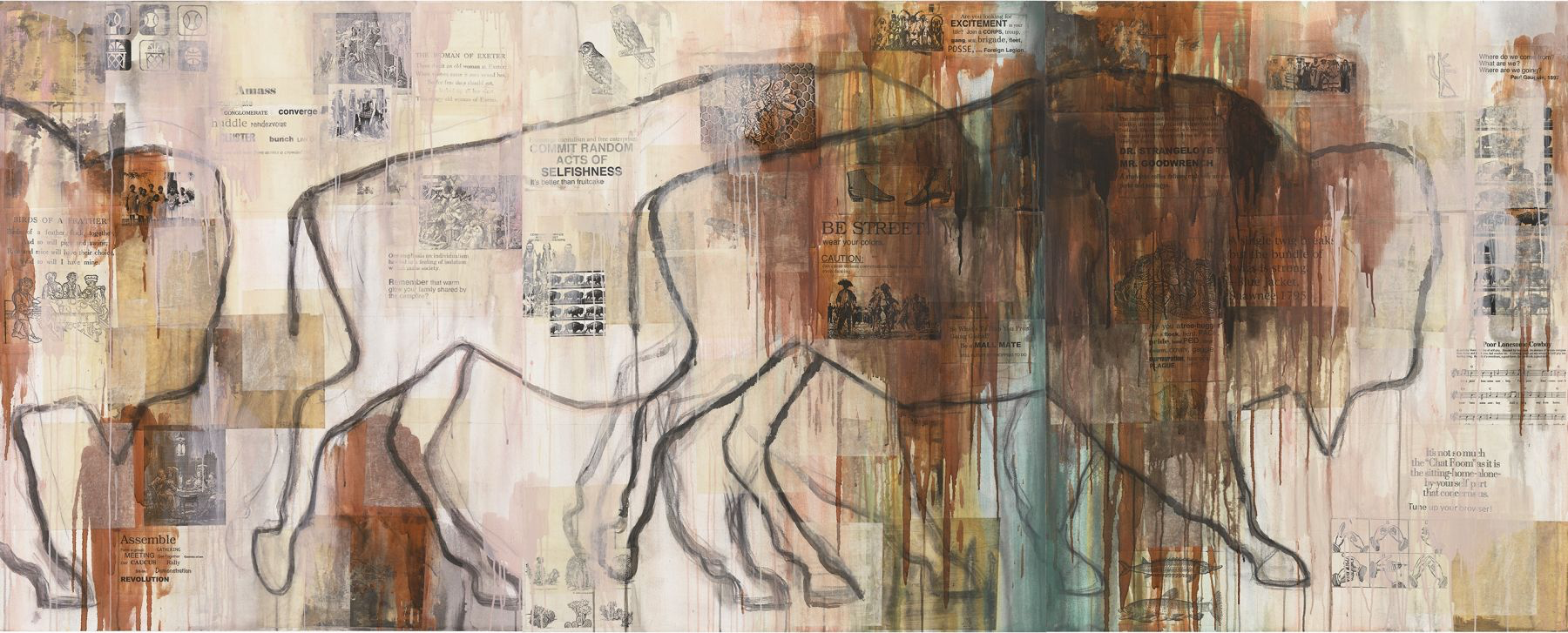

I often paint Flathead symbols in six-feet scale, such as bison, horses, canoes, men’s vests, women’s cutwing dresses and tipis filled with newspaper clippings from our tribal newspaper, the CharKoosta. No way can this work be mistaken for other than “The Last Best Place.”

Smith: “A national treasure”

Although she has long resided in New Mexico, Montana “is always where I circle back to,” says Smith.

She’s produced several curatorial projects here and was a founder of the Montana Indian Contemporary Art organization that promoted original art making and events on reservations in Montana. She has donated 45 artworks to the Missoula Art Museum (making it the largest holding of her work in any U.S. museum), which became the cornerstone for MAM’s Contemporary American Indian Art Collection, and in turn inspired the establishment of its Lynda M. Frost Contemporary American Indian Art Gallery.

MAM executive director Laura Millin, who nominated her the Governor’s Arts Award, who has worked with Smith “as an exhibiting artist, curator, passionate educator, donor, arts advocate and advisor,” notes that “Jaune has been on the forefront of bringing contemporary Native art into the contemporary art of the world.”

Montana artist Anne Appleby calls Smith “a national treasure for her brilliance and devotion to art and the human community.” And associate art professor Jennifer Combe, who annually teaches approximately 80 elementary education majors and eight art education majors at the University of Montana, says Smith’s work “is the cornerstone of my curriculum and the primary artist my students remember and honor … Her work empowers University of Montana education students because it tells stories from peoples that have previously been silenced, allowing educators to teach social studies and art from diverse perspectives.”

Cameron Decker, head of the Fine Arts Department at Salish Kootenai College in Pablo, introduces students to Smith’s work in his class in Contemporary American Indian Art History.

“Besides the techniques she employs and the thoughtful content contained in her work, I introduce her for inspiration,” he writes. “Inspiration that I felt upon seeing my first large-scale painting of hers some time ago in a museum in New Mexico. The kind of inspiration that gives us hope for the future of Native people. Hope that drives us as Salish people forward, realizing the possibilities for our expression and voice.”

– Kristi Niemeyer