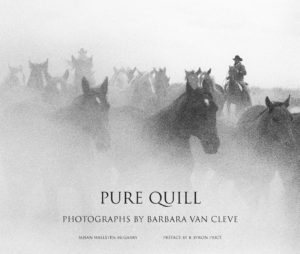

“Pure quill” – in the vernacular of the West – means authentic. A new collection of photographs by Big Timber artist Barbara Van Cleve embodies – both in artistry and content – the meaning of those words.

Two Rivers Gallery in Big Timber celebrates both the artist and her book with a reception, 5-7 p.m. Oct. 27, and an exhibit of her iconic photographs, continuing through Nov. 11. The Big Timber native will be on hand at the opening to sign books and discuss the images.

“Half measures and artifice have no place in her oeuvre,” writes B. Byron Price in the preface to Pure Quill. “Honesty, consistency, and versatility are its hallmarks, and pride of place, her brand.”

The collection spans Van Cleve’s broad, colorful career, and offers insight into her early life on the family dude ranch, the years she spent in academia, and her evolution as a photographer. It took top honors as Best Adult Book and Best Art Book in the 2016 New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards (it was published by the University of New Mexico Press).

Her parents, Spike and Barbara Van Cleve, gave their daughter a Brownie Junior box camera when she was 11, and a darkroom kit a year later. “When you are raised on a ranch, you mind the landscape; you notice the sky; you look for what the weather is doing; and you keep an eye on your cattle, your horses, your companions, and all the elements around you.”

Those early lessons in paying attention infiltrated her work as an image-maker. Now in her early 80s, the artist is still making photographs with care, refinement and passion.

Her images reflect an insider’s ease. She clearly knows where to plant herself (often in the saddle), and how to convey the scene unfolding before her lens: cattle and horses, backlit or with outlines etched in light, sharply focused or intentionally softened; and rough-hewn westerners, intent on the job at hand, whether it’s branding a calf, disembarking a bucking horse, or pulling a brisket from the oven.

“I’m not preserving the West of myth; I’m preserving the West of reality,” she says.

Always, her images encompass two ever-changing constants: the undulating landscape, its “layers, patterns, and textures,” and the astonishing sky, which she views as “another way of talking about light … And all photography is about light.”

The book also illustrates her tenacity and success as a businesswoman. In addition to freelancing, she started a large stock photo business in Chicago that boasted more than a half million images. After moving to Santa Fe in 1980 – wooed by New Mexico’s famous light and its history as a haven for artists and photographers – Van Cleve started a greeting-card company called Abertura.

In the late 1980s, determined to document the contributions women make to ranching, she spent four years traveling to ranches in virtually every western state, shooting film and interviewing women ranging in age from 22 to 80. The images and conversations were eventually distilled in her first book, Hard Twist, Western Ranch Women, which includes 122 photographs from 13 ranches.

“People perceive of ranching in the West as women-less,” writes Van Cleve. “I would like to think that my contribution changes that perception.”

She also collaborated with Montana poet Paul Zarzyski on Roughstock Sonnets and All This Way for the Short Ride, and paired up with author Marc Talbert in Holding the Reins: A Ride Through Cowgirl Life.

The Andrew Smith Gallery in Santa Fe has housed six solo shows of her work over three decades. Gallery owner Smith, one of the early proponents of her work, calls her “the real deal” and places her in a pantheon of western photographers that includes two other notable Montanans: L.A. Huffman and Evelyn Cameron.

Her images capture “the true grandeur and enthralling isolation and toughness of the American West,” says Smith.

The book concludes with Van Cleve’s own short treatise on her art, “Taking and Making a Photograph.” Photography “is a means of revealing and sharing compassion for, information about, and the resonating memories of the thing observed. All vision, which includes photographic vision, has a spiritual content. I believe passionately that this kind of vision honors the single moments of human existence, no two of which are the same.”

In the foreword, Livingston author Tim Cahill notes that although she travels widely, Van Cleve returns every summer to her home on the edge of the Crazy Mountains.

“She could no more leave her home state than she could give up breathing,” he writes. “Montana is the site of her lifelong vision quest, and I’m not the only person who likes to think of her as its guardian spirit.”

– Kristi Niemeyer