The jacket of Victor Charlo’s Dirty Corner Poems and Other Stories covers the basics: he’s a descendant of Salish Chief Charlot who signed the Hellgate Treaty; he studied theology at Gonzaga University; and he lives at the Old Agency just outside of Dixon, on the Flathead Indian Reservation. A deeper look reveals even more facets to the poet, activist and father. For instance, his brother served in World War II, and died at Iwo Jima. For many years Charlo worked at the Kicking Horse Job Corps and started what would eventually become Two Eagle School in Pablo.

Throughout his life, Charlo has been an advocate for Indigenous issues and for those affected by poverty, including his work with The Poor People’s Campaign. Charlo’s youngest daughter, April, often translates his work into Salish, most notably his first collection, Put Sey, which roughly translates as “Good Enough.”

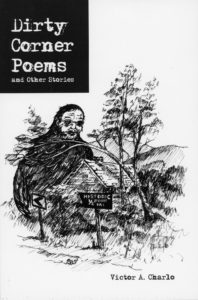

The book’s namesake, Dirty Corner, is a deadly turn south of Arlee where several fatal car crashes have occurred; it’s also a derogatory term for the neighborhood where “the Indians” live. The treacherous bend on Highway 93 sets the stage for this collection and its themes, ranging from memory to progress, and the dichotomy between what was and is. In accessible prose, Charlo reflects on his eight decades, exploring life cycles, rural life, divinity, weather, the elements and family.

Charlo’s connection to place, especially the Flathead Reservation, is revealed in imagery-rich lines. “Outside my door golden eagles fly/ upriver as we watch in awe” he writes in “Wild Things at Dixon Agency. “Big birds you come hither/ flapping your wings in water/honking …”

In “The July, 1994” he brings to life moments with family and sacred events: “My Salish synapses/ are firing the Old sounds/ as I try to talk perfect English to the Dame of Arlee powwow/ I’m not doing too good.”

Many of Charlo’s friends and mentors are immortalized too. For example, in “A Hugo Ride,” the author recalls one of Montana’s best-known poets, Richard Hugo: “Dick had no question of what they were doing/ he just knew/ no big explanation or anything/ He wanted me to know a lot was going on by saying very little.”

Charlo also meditates on social issues, especially as they apply to the Salish in Montana. In “Moving In (Fast Wind),” “A Modest Proposal,” and “Takeover” the author reflects on the fate of bison, and the effects of religion, boarding schools and the arrival of white people upon Indigenous people over the past several hundred years.

“Dirty Corner” is referenced repeatedly as a place of solace, despair, condemnation, disgrace, shame, anger and honesty. In the end, that treacherous corner represents home. For anyone who has ever been caught between shame and pride for where they’re from, Victor Charlo’s latest collection, published by Many Voices Press, is a must read.

– Brynn Cadigan